Case Report

Implications of entomological evidence during the investigation of five cases of violent death in Southern Brazil

Patrícia J Thyssen1*, Marina FK Aquino1, Natane CS Purgato1, Edmilson Martins2, Alexandre A Costa2, Carolina GP Lima2 and Claudemir R Dias2

1Laboratory of Integrative Entomology, Department of Animal Biology, IB, University of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo State, Brazil2Criminalistic Institute, Superintendência da Polícia Técnico-Científica do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo State, Brazil

*Address for Correspondence: Patricia Jacqueline Thyssen, Laboratory of Integrative Entomology, DBA-IB, UNICAMP Rua Monteiro Lobato, 255 PC 13083-862 Barão Geraldo, Campinas, SP, Brazil, Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 02 January 2018; Approved: 10 January 2018; Published: 11 January 2018

How to cite this article: Thyssen PJ, Aquino MFK, Purgato NCS, Martins E, Costa AA, et al. Implications of entomological evidence during the investigation of five cases of violent death in Southern Brazil. J Forensic Sci Res. 2018; 2: 001-008. DOI: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001013

Copyright License: © 2018 Thyssen PJ, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Blowflies; Flesh fly; Necrophagous dipterans; Forensic entomology; Postmortem interval

Abstract

In homicide cases, knowledge about time of death is important as it directs police investigation towards the discovery of authorship, including or excluding suspects of a crime, and determining nature of death. In Brazil, entomological evidence is still neglected by official forensic organizations and for this reason cases using insects to estimate post-mortem interval (PMI) are still rare. Dipteran specimens collected and analyzed by the staff of Criminalistics Institute (CI) from São Paulo State, Brazil, made it possible to elucidate circumstances of the death, including suspects to the crime scene, in five occurrences involving discovery of cadavers. In all cases, blowflies were collected and were identified as belonging to species Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819), Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794), Chrysomya putoria (Wiedemann, 1830), Hemilucilia semidiaphana Rondani, 1850 and Lucilia eximia (Wiedemann, 1819) (Diptera: Calliphoridae), while only in one case Sarcophagidae (Diptera) flies were also collected. PMI estimate was calculated taking into account laboratorial developmental rate data of mentioned species on the environmental temperature on which bodies and insects were exposed, along with comparisons to field research previously conducted in those areas. Based on larval age and behavior, the course of the investigation had changed, pointing to the crime author (case I), as well as the nature of the crime (cases I-III) and associated suspects to the criminal act (cases IV-V). Results show how promising is the use of entomological evidence during investigations of violent deaths.

Introduction

One of Forensic Entomology major contributions to legal purposes is the use of ecological and developmental data of necrophagous insects to estimate post-mortem interval (PMI) in crime investigations [1,2], allowing investigators to include or exclude probable suspects as authors of a homicide [3], or defining the manner of death that can be at first unknown or doubtful.

In São Paulo state, Brazil, processing of crime scenes related to violent death occurs in two steps. The first consists on an exam done by the crime scene investigator from Criminalistics Institute (CI) and involves evidence collection from the scene itself as well as information about position of the body and its external wounds. During this process, not only characteristics of the scene and its adjacent areas are obtained, but also collection of all material evidence such as biological stains, fire gun projectiles, fingerprints or any other element that can be useful to determine materiality, cause or authorship of the crime.

The second step takes place when the corpse is taken to Medico Legal Institute (MLI), when the medical officer can perform an autopsy with the objective to describe body physical characteristics, place, type and orientation of internal and external wounds, in order to establish the cause of death. Summarizing, entomological evidence can be obtained in one of the two steps: by CI officers during scene processing or by MLI officers during autopsy. Transportation of the cadaver from crime scene to MLI could represent a risk of losing some of the necrophagous fauna, mainly post feeding larvae (those that migrate spontaneously to pupate) and pupae, so it is highly recommended to collect them during crime scene exam. Moreover, while in the crime scene, it is still possible to register insects’ behavior, in and around the corpse, adding information to PMI estimate.

Although the proved utility of entomological specimens in solving crimes [4-30], such evidences are still neglected during crime scene exam and autopsy in Brazil. Probably, it is due to the lack of knowledge about the importance of entomological evidences and disclosure about its applications, justifying why case reports using insects to estimate PMI are still rare in the country [31-36]. In order to show real possibilities for using entomological evidence in police investigations, we present here five cases attended by CI and MLI officers from three cities from São Paulo State, Southern Brazil. In these cases, crime scene and autopsy exams were enriched by analysis of Diptera from decomposing corpses, allowing elucidation of circumstances of the death, including suspects to the crime scene.

Practice process

When present in the crime scene, adult flies were collected using an entomological net, then transferred to a killing jar containing ether as toxic agent [37]. Collected specimens were taken to the laboratory and identified based on morphological characteristics described in identification keys [38-40].

Larvae were collected from cadavers using forceps and taken to the lab for identification [41] and estimation of PMI [16]. In each case, some larvae were transferred to vials containing 70% ethanol, being kept permanently as a testimony in the Laboratory of Integrative Entomology at UNICAMP. The other part of the specimens was collected and transferred to vials containing raw meat and were brought alive to laboratory, then were weighted and had their larval instar observed under stereoscopic microscopy. After that, they were kept in screened plastic cages containing artificial diet [42,43], and maintained in a controlled-temperature room at 25±1°C, 60%±10% relative humidity and a 12-h photoperiod. When larvae reached the post-feeding stage, they were transferred to another vial containing sawdust for pupation. Emerged adults were identified [38-40]. Environmental data (temperature and humidity) was obtained from the nearest weather station in the scene or measured with a digital thermometer.

Cases Report

Case I: Natural Death or Homicide?

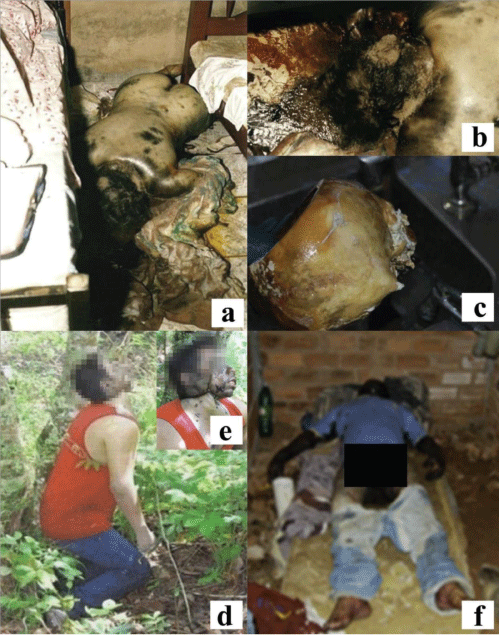

A body of a 58 years-old woman was found lying on her ventral side near a bed inside a house located in the urban area of the city of Franca, São Paulo State, Brazil. She was in decay stage of decomposition (Figure 1A-C), without any apparent external wounds that could indicate violence detention, nor any sign of breaking into door or windows. According to information gathered in the scene, the victim lived alone. Based on the post mortem events, the medical officer estimated PMI in seven days. Absence of apparent injuries, associated to heart disease history of the victim, led the officers to conclude the case as a natural death, fact not proven by anatomopathological observations. Facing these doubts, an exhumation of the body was done a few weeks later to check cause and means of death, which led to a police inquiry to elucidate these facts and reviewing new details. During the crime scene analysis, the investigator had registered the presence of a larvae mass in the occipital region; insects first colonize primarily natural orifices, and the presence of this mass associated with the position of the body suggests that the wound was caused shortly before death, not corresponding to a natural accident.

Figure 1: Decay stage of decomposition observed when the corpses (cases 1 to 3) were discovered. a. Position of the victim’s corpse (case 1) when it was discovered. b. Larval mass in the victim’s head region (case 1). c. Absence of bone fracture (case 1). d. Position of the victim’s corpse when it was discovered (case 2). e. Neck detail (case 2). f Body discovered inside an abandoned house without any ante mortem injury (case 3).

Adult blowflies emerged in laboratory were identified as Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Data obtained in laboratory regarding parameters related to larval weight and developmental time [44], corroborated seven days PMI that had been calculated by the forensic doctor through observation of the livor and rigor mortis. Insect behavior provided evidences that death could not have been natural, and PMI based on post mortem events with entomological data concordance led investigators to dig deeper. Therefore, a suspect who knew the victim and had been seen around the victim’s house in the time of her death was arrested. He confessed trying to rape the victim, and while trying to subdue her, the back of her head was hit against the floor and she fainted. Thus, he rearranged things back to their place and locked the door using his copy of the house key, and then fled the scene.

Case II: Suicide or Homicide?

A 30 years-old man was discovered hanging from a tree (Figures 1D,1E) in a rural area next to a forest, in the city of Batatais, São Paulo State, Brazil. He was reported missing by his family for at least seven days. According to criteria adopted by França [45], the corpse was between bloat and decay stages of decomposition, with presence of skin bubbles, bloated abdomen, protrusion of eyes and tongue. Bodies found in the previously mentioned position do not have a usual decomposition process. Once evolution of chemical and physical changes of the body after death is one of the most used methods to determine the time passed since the death [46], estimate PMI based only on post mortem events is less accurate or not even advisable.

Eggs and third instar larvae were collected. Specimens, identified as Hemilucilia semidiaphana (Rondani, 1850) (N=24) and C. albiceps (N=228), emerged in 12 and eight days, respectively. Crime scene temperature was of 25 ºC on the day the body was discovered. The total developmental time registered in literature for this temperature is approximately of 16 days for H. semidiaphana [46] and 12 days for C. albiceps [45]. Taking into account that the immatures of both species remained in laboratory for 12 days, we can conclude that the victim presented a PMI of four days. A study using animal models [48] conducted near the area where the body was found showed that fauna collected from the corpse was commonly registered in that environment.

The time line of the investigation based on information reported previously by the family changed from the data provided by insects. New efforts of the police led them to ascertain that victim’s friends had seen him accompanied by five suspicious people five days before the discovery of the corpse. Thus, nature of death, firstly classified as suicide, could be, in fact, a case of intentional homicide that required further investigations.

Case III: Murder or Natural Death?

A 60 years-old homeless man was found lying facing down inside an abandoned house (Figure 1F) in the center of the city of Franca, São Paulo State, Brazil, in fresh stage of decomposition. He had last been seen alive approximately six days before, accompanying another person, so an accurate PMI estimate was relevant to elucidate if there was a murder suspect. Crime scene temperature, measured using a digital thermometer, was of 23oC. Third instar larvae were collected, and adults emerged after 14 days, being identified as C. albiceps (N=10). Literature data [44,46] indicate that under conditions above, this species completes its development in 18 days. Based on these studies, a PMI of four days was obtained. Instead of a murder, as previously contemplated, the verdict was of natural death, due to the impossibility of involvement of the only suspect in the criminal scene.

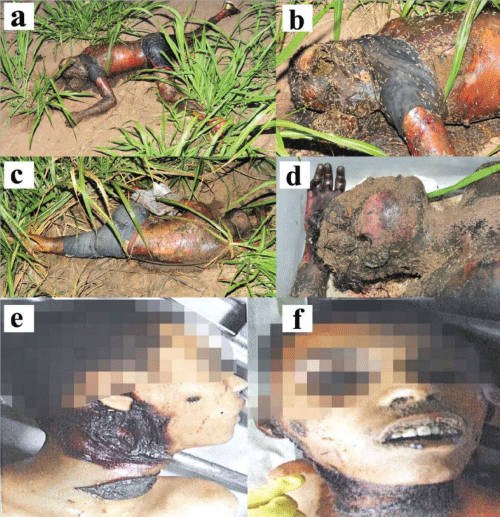

Case IV: Suspects Association to the Crime

Two 20’s and 30’s years-old male corpses were discovered laying down in the middle of a sugar cane plantation in the city of Cosmópolis, São Paulo State, Brazil, in decay process of decomposition (Figures 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D), presenting several gunfire shots throughout the bodies. Crime scene personnel could not find any identification card during the processing of the crime scene. However, they noticed that the corpses were colonized by some dipteran larvae. Larvae collected from corpse 1 (Figures 2A,2C) were identified as belonging to species Chrysomya putoria (Widemann, 1830) (N=18) with 21.7 mg mean weight. Larvae obtained from corpse 2 (Figures 2B,2D) were identified as being of two different blowflies species: Chrysomya megacephala [49] with 66.7 mg mean weight, and C. albiceps with 29.8 mg mean weight. Calculation of PMI was done taking into account larval weight, environment temperature data and laboratorial data on developmental rate studies of the species of forensic importance [44,49-51]. Age, in hours, estimated to each species was 95 to C. putoria, 94 to C. megacephala and 77 to C. albiceps.

Later on, this case was related to a missing person occurrence of two relative male individuals, a 28 years-old uncle whose physical characteristics, e.g, an amputated arm, were similar to those from corpse 1 and a 24 years old nephew that was recognized by his mother as corpse 2. They were reported missing about four days before discovery of the cadavers. Considering age of the larvae of C. putoria and C. megacephala and a possibility of nocturnal oviposition, as it had been reported for other species of blowflies by Greenberg and by personal observation of the authors [52], we can conclude that time of death was close to the time the subjects went missing. Based on this information, people last seen with the victims were included as the main suspects of the crime.

Figure 2: Decay stage of decomposition observed when the corpses (cases 4 and 5) were discovered. a. and c Cadavers of two young male identified as corpse 1 and as corpse 2, respectively (case 4). b and d Detail of larvae massively colonizing natural orifices and all corpse (case 4). e. Lateral view of the young man’s body with wounds on the right side of the neck (case 5). f. Fly larvae colonizing natural orifices and wounded trachea (case 5).

Case V: Legal Medicine PMI x Entomological PMI

A 20’s man corpse was found lying on his back on the sidewalk of a street located in the east zone of the city of São Paulo, São Paulo State, Brazil. According to medical officer notes, he had wounds caused by a sharp object on the right side of the neck (Figures 2E,2F) and also on his right hand, which were determined as cause of death. The body was in fresh stage of decomposition and, considering post mortem processes, time of death was determined around 48 hours. The victim was seen alive two days before the discovery of his corpse.

During autopsy, the medical examiner also noticed some fly larvae colonizing the wounds, eyes, mouth and trachea, which were collected and put in the vials containing 70% alcohol. At the laboratory, the material was identified and weighted to confirm if that the age of larvae collected was compatible with the PMI estimated by medico-legal means.

Larvae collected from wounds and eyes were of the species Lucilia eximia (Wiedemann, 1819) and the ones collected from the mouth and trachea were identified as belonging to Sarcophagidae family. Due to the difficulty to identify larvae of Sarcophagidae to the species level (especially since there are not many descriptions of the immature stages of this family in the literature), the chance of error in the calculation of the PMI is increased. Regarding this, L. eximia larvae were chosen to estimate the PMI. Their mean weight was of 0.18 mg and they were between the first and second larval instar. Estimated age was of 42.8 hours, and was calculated using a regression equation based on development of this species [26,53]. This finding corroborates with the PMI estimated by the medical officer, i.e., the death would have occurred approximately two days before the corpse was found. Additionally, it demonstrates that estimates of PMI based on entomological data are as important as those based on decomposition phenomena.

Discussion

Using the biology of necrophagous insects as forensic evidence intended to solve crimes is bringing promising results, once collection and analysis of entomological matter provide relevant information, not only to estimate PMI, but also to comprehend circumstances related to suspicious death, specially in cases where advanced stage of decomposition of the corpse make identification of wounds more difficult.

This applicability of entomological evidence in police investigations justifies the need of training and improvement of crime scene experts in collecting methods, analysis and interpretation of entomological data, demanding an implementation of specialized laboratories in brazilian Criminalistics Institutes. In conclusion, we observed that rearing conditions can have a major impact on the developmental time of dipterans and certainly, there are still more factors, e.g. migration, not considered in this study, which could be measured. Data obtained from different tissues may fill some of the gaps in knowledge of their nutritional requirements, dietary spectrum and differential larval growth of the five blowfly species studied here, which may be useful to improve PMI estimates.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by FAPESP (The State of São Paulo Research Foundation), grant numbers 05/54480-7.

References

- Amendt J, Krettek R, Zehner R. Forensic Entomology. Naturwissenschaften. 2004; 91: 51-65. Ref.: https://goo.gl/RoJ5xq

- Huntington TE, Higley LG, Baxendale FP. Maggot Development During Morgue Storage and Its Effect on Estimating the Post-Mortem Interval. J Forensic Sci. 2007; 52: 453-458. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tJJzeY

- Byrd JH, Castner JL. Forensic Entomology-The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations. CRC Press. 2010; 705. Ref.: https://goo.gl/dGeWPv

- Goff ML. Estimation of postmortem interval using arthropod development and succession patterns. Forensic Sci Rev. 1993; 5: 81-94. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tKYqcm

- Goff ML, Odom CB, Early M. Estimation of post-mortem interval by entomological techniques: a case study from Oahu, Hawaii. Bull Soc Vector Ecol. 1986; 11: 242-246.

- Lord WD, Catts EP, Scarboro DA, Hadfield DB. The green blow fly Lucilia illustris (Meigen) as an indicator of human post-mortem interval: a case of homicide from Fort Lewis, Washington. Bull Soc Vector Ecol. 1986a; 11: 271-275.

- Lord WD, Johnson RW, Johnston R. The blue bottle fly Calliphora vicina (Erythrocephala) as an indicator of human post-mortem interval: a case of homicide from suburban Washington. DC Bull Soc Vector Ecol. 1986b; 11: 276-280.

- Goff ML, Odom CB. Forensic Entomology in the Hawaiian Islands-Three cases studies. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1987; 8: 45-50. Ref.: https://goo.gl/RrWpNp

- Lord WD, Goff ML, Adkins TR, Haskell NH. The black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) as a potential measure of human postmortem interval: observations and case histories. J Forensic Sci. 1994; 39: 215-222. Ref.: https://goo.gl/uy4Ej8

- Benecke M. Six forensic entomology cases: description and commentary. J Forensic Sci. 1998; 43: 797-805. Ref.: https://goo.gl/e8d935

- Oliva A. Insects of forensic significance in Argentina. Forensic Sci Int.2001; 120: 145-154. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1HwSQz

- Sukontason KL, Sukontason K, Narongchai P, Lertthamnongtham S, Piangjai S, et al. Chrysomya rufifacies (Macquart) as a forensically-important fly species in Thailand: A case report. J Vector Ecol. 2001; 26: 162-164. Ref.: https://goo.gl/d81CeP

- Grassberg M, Friedrich E, Reiter C. The blowfly Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) as a new forensic indicator in Central Europe. Int J Leg Med. 2003; 117: 75-81. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ECKsn6

- Andrade HTA, Varela-Freire AA, Batista MJA, Medeiros JF. Calliphoridae (Diptera) Coletados em Cadáveres Humanos no Rio Grande do Norte. Neotrop Entomol. 2005; 34: 855-856. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pBMw1m

- Arnaldos MI, García MD, Romera E, Presa JJ, Luna A. Estimation of postmortem interval in real cases based on experimentally obtained entomological evidence. Forensic Sci Int. 2005; 149: 57-65. Ref.: https://goo.gl/D4ti9a

- Shin SE, Jang MS, Park JH, Park SH. A Forensic Entomology Case Estimating the Minimum Postmortem Interval Using the Distribution of Fly Pupae in Fallow Ground and Maggots with Freezing Injury. Korean J Leg Med. 2015; 39: 17-21. Ref.: https://goo.gl/U68EC6

- Sukontason KL, Narongchai P, Sukontason K, Methanitikorn R, Piangjai S. Forensically important fly maggots in a floating corpse: the first case report in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2005; 88: 1458-1461. Ref.: https://goo.gl/e1pCyK

- Sukontason K, Narongchai P, Kanchai C, Vichairat K, Sribanditmongkol P, et al. Forensic entomology cases in Thailand: A review of cases from 2000 to 2006. Parasitol Res. 2007; 101: 1417-1423. Ref.: https://goo.gl/mdnYUB

- Manlove JD, Disney RHL. The use of Megaselia abdita (Diptera: Phoridae) in forensic entomology. Forensic Sci Int. 2008; 175: 83-84. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1ovQuv

- Vanin S, Tasinato P, Ducolin G, Terranova C, Zancaner S, et al. Use of Lucilia species for forensic investigations in Southern Europe. Forensic Sci Int. 2008; 177: 37-44. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UvX1GF

- Wallace JR, Merritt RW, Kimbirauskas R, Benbow ME, McIntosh M. Caddisflies assist with homicide case: determining a postmortem submersion interval using aquatic insects. J Forensic Sci. 2008; 53: 219-221. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tZYyHg

- Oliveira TC, Vasconcelos SD. Insects (Diptera) associated with cadavers at the Institute of Legal Medicine in Pernambuco, Brazil: Implications for forensic entomology. Forensic Sci Int. 2010; 198: 97-102. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1GBrvE

- Al-Mesbah H, Al-Osaimi Z, El-Azazy OME. Forensic Entomology in Kuwait: The first case report. Forensic Sci Int. 2011; 206: 5-26. Ref.: https://goo.gl/rT2dJT

- Barros M, Wolff M. Initial study of arthropods succession and pig carrion decomposition in two freshwater ecosystems in the Colombian Andes. Forensic Sci Int. 2011; 212: 164-172. Ref.: https://goo.gl/kbPh12

- Cherix D, Wyss C, Pape T. Occurrences of flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) on human cadavers in Switzerland, and their importance as forensic indicators. Forensic Sci Int. 2012; 220: 158-163. Ref.: https://goo.gl/edgWtQ

- Sanford MR, Whitworth TL, Phatak DR. Human Wound Colonization by Lucilia eximia and Chrysomya rufifacies (Diptera: Calliphoridae): Myiasis, Perimortem, or Postmortem Colonization? J Med Entomol. 2014; 51: 716-719. Ref.: https://goo.gl/cmK9JM

- Patitucci LD, Mulieri PR, Domínguez MC, Mariluis JC. An inventory of saprophagous Calyptratae (Insecta: Diptera) in urban green spaces of Buenos Aires City. Rev Mus Arg Cienc Nat. 2015; 17: 97-107. Ref.: https://goo.gl/VRh2fT

- Bala M, Sharma A. Postmortem Interval Estimation of Mummified Body Using Accumulated Degree Hours (ADH) Method: A Case Study from Punjab (India). J Forensic Sci and Criminal Inves. 2016; 1: 1-5. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pQ5gJ6

- Hayman J, Oxenham M. Peri-mortem disease treatment: a little known cause of error in the estimation of the time since death in decomposing human remains. Austr J Forensic Sci. 2016; 48: 178-185. Ref.: https://goo.gl/TUihir

- Talebzadeh F, Ghadipasha M, Gharedaghi J, Yeksan N, Akbarzadeh K, et al. Insect Fauna of Human Cadavers in Tehran District. J Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2017; 11: 363-370. Ref.: https://goo.gl/a5Xfe1

- Oliveira-Costa J, Mello-Patiu CA. Application of forensic entomology to estimate of the post mortem interval (PMI) in homicide investigations by the Rio de Janeiro Police Department in Brasil. Aggrawal’s I J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2004; 5: 40-44. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hdr4dT

- Pujol-Luz JR, Marques H, Ururahy-Rodrigues A, Rafael JA, Santana FHA, Arantes LC, et al. A forensic entomoly case from the Amazon rain forest of Brazil. J Forensic Sci. 2006; 51: 1151-1153. Ref.: https://goo.gl/oFyczB

- Pujol-Luz JR, Francez PAC, Ururahy-Rodrigues A, Constantino R. The black soldier-fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera, Stratiomiidae), used to estimate the postmortem interval in a case in Amapá state, Brazil. J Forensic Sci. 2008; 53: 476-478. Ref.: https://goo.gl/r5FZz6

- Kosmann C, Macedo MP, Barbosa TAF, Pujol-Luz JR. Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann) and Hemilucilia segmentaria (Fabricius) (Diptera, Calliphoridae) used to estimate the postmortem interval in a forensic case in Minas Gerais, Brazil Rev Bras Entomol. 2011; 55: 621-623. Ref.: https://goo.gl/63sQdH

- Vasconcelos SD, Soares TF, Costa DL. Multiple colonization of a cadaver by insects in an indoor environment: first record of Fannia trimaculata (Diptera: Fanniidae) and Peckia (Peckia) chrysostoma (Sarcophagidae) as colonizers of a human corpse. Int J Leg Med. 2014; 128: 229-233. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hZSMvS

- Vairo KP, Caneparo MFC, Corrêa RC, Preti D, Moura MO. Can Sarcophagidae (Diptera) be the most important entomological evidence at a death scene? Microcerella halli as a forensic indicator. Rev Bras Entomol. 2017; 61: 275-276. Ref.: https://goo.gl/6N4Bdu

- Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. Borror and DeLong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects. Thomson Brooks/Cole, USA, 864.

- Carvalho CJB, Mello-Patiu CA. Key to the adults of the most common forensic species of Diptera in South America. Rev Bras Entomol. 2008; 52: 390-406. Ref.: https://goo.gl/cp5bXu

- Grella MD, Thyssen PJ. Chave taxonômica interativa para espécies de dípteros califorídeos.

- Grella MD, Savino AG, Paulo DF, Mendes FM, Azeredo-Espin AML, et al. Phenotypic polymorphism of Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) may lead to species misidentification. Acta Trop. 2015; 141: 60-72. Ref.: https://goo.gl/BBicgb

- Thyssen PJ. Keys for identification of immature insects in.

- Amendt J, Campobasso CP, Goff ML Grassberger M. Current concepts in Forensic Entomology. Springer, London. 25-42.Ref.: https://goo.gl/nYoZyF

- Estrada DA, Grella MD, Thyssen PJ, Linhares AX. Taxa de desenvolvimento de Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) em dieta artificial acrescida de tecido animal para uso forense. Neotrop Entomol. 2009; 38: 203-207. Ref.: https://goo.gl/q82XZk

- Rabelo KCN, Thyssen PJ, Salgado RL, Araújo MSC, Vascon celos SD. Bionomics of two forensically important blowfly species Chrysomya megacephala and Chrysomya putoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) reared on four types of diet. Forensic Sci. Int. 210: 257-263.

- Queiroz M.M.C., Milward-de-Azevedo W.M.V. (1991) Técnicas de criação e alguns aspectos da biologia de Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann) (Diptera, Calliphoridae), em condições de laboratório. Rev. Bras. Zool. 2011; 8: 75-84. Ref.: https://goo.gl/GH812R

- França GVF. Medicina Legal. Guanabara-Koogan, Rio de Janeiro. 2008; 210. Ref.: https://goo.gl/zHhnr6

- Campobasso CP, Vella G, Introna F. Factors affecting decomposition and Diptera colonization. Forensic Sci Int. 2001; 120: 18-27. Ref.: https://goo.gl/akFo5A

- Thyssen PJ. Caracterização das formas imaturas e determinação das exigências térmicas de duas espécies de califorideos (Diptera) de importância forense. 2017.

- Martins E. Análise dos processos de decomposição e sucessão ecológica em carcaças de suíno (Sus scrofa L.) mortos por disparo de arma de fogo e overdose de cocaína e protocolo de procedimento diante de corpo de delito.

- Wells JD, Kurahashi H. Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) development: rate, variation, and the implications for forensic entomology. Jpn J Sanit Zool. 1994; 45: 303-309. Ref.: https://goo.gl/bHHGZz

- Souza AM. Biologia em laboratório dos estágios imaturos de espécies de Calliphoridae e Sarcophagidae (Diptera) de importância médico legal na região de Campinas. 1997. Ref.: https://goo.gl/XDxgRK

- Anderson GS. Determining time of death using blow fly eggs in the early postmortem interval. Int J Leg Med. 2004; 118: 240-241. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jUHrV8

- Greenberg B. Nocturnal oviposition behavior of blow flies (Diptera Calliphoridade). J Med Entomol. 1990; 27: 807-810. Ref.: https://goo.gl/PNsQuW

- Adair TW. Calliphora vicina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) collected from a human corpse above 3400 m in elevation. J Forensic Sci. 2008; 53: 1212-1213. Ref.: https://goo.gl/itKk3o

- Farrell JF, Whittington AE, Zalucki MP. A review of necrophagous insects colonizing human and animal cadavers in south-east Queensland, Australia. Forensic Sci Int. 2015; 257: 149-154. Ref.: https://goo.gl/AFfmTa

- Moopayak K, Vogtsberger RC, Olson JK, Sukontason KL. Forensic entomology cases in Thailand: a review of cases from 2000 to 2006. Parasitol Res. 2007; 101: 1417-1423. Ref.: https://goo.gl/6bHsVG