Abstract

Review Article

Toxic Components in Baby Care Products – A Comprehensive Review

Avinav Jha*

Published: 08 April, 2025 | Volume 9 - Issue 1 | Pages: 029-036

Background: In addition to being used to keep babies clean and comfortable, baby care products may also include hazardous substances that are harmful to the baby’s health. To safeguard the health of new-borns, it is crucial to understand the potential toxins included in baby care products.

Objective: This paper focuses on the very bothering aspect of baby care products. The objective of this study is to identify and summarise the effect of toxicants present in baby care products including their source, exposure, toxicity, and adverse effects on infants.

Methods: Utilizing several internet databases including various open source, including PubMed, Scopus, and research gate, a thorough literature search was carried out. The review covered articles that were written in English and published in last fifteen years. Studies reporting on the sources, effects, and potential exposure pathways of toxicants found in infant care products have been included.

Result: The study deals with a list of harmful toxicants like phthalates, asbestos, parabens, heavy metals, sodium laurel sulphates, etc., and their sources and modes of exposure. Exposure to toxicants such as phthalates, asbestos, parabens, heavy metals, and sodium laurel sulphates can lead to cancer, developmental disorders, and endocrine disruption.

Conclusion: It can be concluded that baby care products are having adverse effects on infants, on their skin or health, or in other ways. To avoid the same, the root cause of it should be avoided, which is the inclusion of toxicant chemicals in such baby care products. Parents and caretakers should be aware of the dangers of toxicant chemicals in baby care products and use non-toxic products to protect their babies' health, while manufacturers should use safer components. Government and authorized agencies should enforce restrictions.

Read Full Article HTML DOI: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001077 Cite this Article Read Full Article PDF

Keywords:

Toxicants; Health risks; Developmental disorder

References

- Lekha SA. Consumer behaviour on baby care products in Madurai district young mothers perspective. 2019. Available from: https://www.vhnsnc.edu.in/img/Invitation/2020-2021/bba/Ph.D_Viva_Voce_BBA_250920.pdf

- Brod BA, Treat JR, Rothe MJ, Jacob SE. Allergic contact dermatitis: Kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015 Nov 1;33(6):605–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.09.003

- Nepalia A, Singh A, Mathur N, Pareek S. Toxicity assessment of popular baby skin care products from Indian market using microbial bioassays and chemical methods. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2018;15(11):2317–24. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13762-017-1556-z

- Visscher M, Narendran V. Neonatal infant skin: Development, structure and function. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2014;14(4):135–41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2014.10.004

- Kuller JMM. Update on newborn bathing. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2014;14(4):166–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2014.10.006

- Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. EXS. 2012;101:133–64. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_6

- Lv C, Hou J, Xie W, Cheng H. Investigation on formaldehyde release from preservatives in cosmetics. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2015;37(5):474–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12212

- Lovschall H, Eiskjaer M, Arenholt-Bindslev D. Formaldehyde cytotoxicity in three human cell types assessed in three different assays. Available from: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/toxinvit

- Ke YJ, Qin XD, Zhang YC, Li H, Li R, Yuan JL, et al. In vitro study on cytotoxicity and intracellular formaldehyde concentration changes after exposure to formaldehyde and its derivatives. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014;33(8):822–30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327113510538

- Yoshida I, Ibuki Y. Formaldehyde-induced histone H3 phosphorylation via JNK and the expression of proto-oncogenes. Mutat Res. 2014 Dec 1;770:9–18. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.09.003

- Prasad HRY, Srivastava P, Verma KK. Diapers and skin care: Merits and demerits. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:907–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02830834

- O’Connor RJ, Sanchez V, Wang Y, Gibb R, Nofziger DL, Bailey M, et al. Evaluation of the impact of 2 disposable diapers in the “Natural” diaper category on diapered skin condition. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019 Jun 1;58(7):806–15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819841136

- Yuan C, Takagi R, Yao XQ, Xu YF, Ishida K, Toyoshima H. Comparison of the effectiveness of new material diapers versus standard diapers for the prevention of diaper rash in Chinese babies: A double-blinded, randomized, controlled, cross-over study. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5874184. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5874184

- Razavi N, Es’haghi Z. Employ of magnetic polyaniline coated chitosan nanocomposite for extraction and determination of phthalate esters in diapers and wipes using gas chromatography. Microchem J. 2018;142:359–66. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2018.07.015

- Ishii S, Katagiri R, Minobe Y, Kuribara I, Wada T, Wada M, et al. Investigation of the amount of transdermal exposure of newborn babies to phthalates in paper diapers and certification of the safety of paper diapers. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;73(1):85–92. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.06.010

- Park CJ, Barakat R, Ulanov A, Li Z, Lin PC, Chiu K, et al. Sanitary pads and diapers contain higher phthalate contents than those in common commercial plastic products. Reprod Toxicol. 2019;84:114–21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2019.01.005

- Zhang SX, Chai XS, Jiang R. Accurate determination of residual acrylic acid in superabsorbent polymer of hygiene products by headspace gas chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2017;1485:20–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2017.01.023

- Hamasaki T. Simultaneous determination of organotin compounds in textiles by gas chromatography-flame photometry following liquid/liquid partitioning with tert-butyl ethyl ether after reflux-extraction. Talanta. 2013;115:374–80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2013.04.041

- Šmajgl D, Obhodaš J. Occurrence of tin in disposable baby diapers. X-Ray Spectrom. 2015;44(4):230–2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/xrs.2609

- Na YR, Kwon HJ, Cho HN, Kim HJ, Park YK, Park SA, et al. Formaldehyde monitoring of hygiene products in domestic market. J Food Hyg Saf. 2020;35(3):225–33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.13103/jfhs.2020.35.3.225

- Liu W, Xue J, Kannan K. Occurrence of and exposure to benzothiazoles and benzotriazoles from textiles and infant clothing. Sci Total Environ. 2017;592:91–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.090

- Makoś-Chełstowska P, Kurowska-Susdorf A, Płotka-Wasylka J. Environmental problems and health risks with disposable baby diapers: Monitoring of toxic compounds by application of analytical techniques and need of education. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2021 Oct 1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2021.116408

- Kwon YS, Choi SG, Lee SM, Kim JH, Kim SG, Lee DY, et al. Improved method for the determination of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) in sanitary napkins. Anal Lett. 2020;53(2):273–89. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00032719.2019.1647226

- Rodriguez KJ, Cunningham C, Foxenberg R, Hoffman D, Vongsa R. The science behind wet wipes for infant skin: Ingredient review, safety, and efficacy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(3):447–54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14112

- Kuller JMM, Zukowsky K. Infant skin care products: What are the issues? Adv Neonatal Care. 2016;16(5 Suppl):S3–12. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/advancesinneonatalcare/abstract/2016/10001/infant_skin_care_products__what_are_the_issues_.2.aspx

- Cahill LJ, Toholka WR, Nixon RL. Contact allergy in children. Med J Aust. 2014;200(4):213.

- Celeiro M, Lamas JP, Garcia-Jares C, Llompart M. Pressurized liquid extraction–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of fragrance allergens, musks, phthalates and preservatives in baby wipes. J Chromatogr A. 2015 Mar 6;1384:9–21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2015.01.049

- Rocha BA, Bocato MZ, Latorraca EF, Ximeneza JPB, Barbosa F. A survey of parabens in commercial baby wipes from Brazil and estimation of daily exposure. Quim Nova. 2020 Apr 1;43(4):442–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21577/0100-4042.20170494

- Brand W, Boon PE, Hessel EVS, Meesters JAJ, Weda M, Schuur AG. Exposure to and toxicity of methyl-, ethyl- and propylparaben: A literature review with a focus on endocrine-disrupting properties [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/en

- Ishiwatari S, Suzuki T, Hitomi T, Yoshino T, Matsukuma S, Tsuji T. Effects of methyl paraben on skin keratinocytes. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27:1–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.1176

- Komamura H, Dor T, Inui S, Yoshikawa K. [No title available]. 1997.

- Singh H, Poulos A. A comparative study of stearic and lignoceric acid oxidation by human skin fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;250(1):171–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(86)90714-9

- Sushmitha C. Baby care–baby care products and harmful ingredients used in baby products. Asian J Pharm Tech Res. 2019. Available from: https://ajptr.com/assets/upload/publish_article/AJPTR_96004.pdf

- Magon S. ISSN 2347-954X (Print) Use of Talcum Powder on Infants and Toddler [Internet]. Vol. 2, Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS. 2014. Available from: https://saspublishers.com/article/7025/download/

- Bergfeld WF, Donald FACP, Belsito V, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, Liebler DC, et al. Safety assessment of talc as used in cosmetics. Final Report. 2013 Apr 12.

- Rohl AN, Langer AM, Selikoff IJ, Tordini A, Klimentidis R, Bowes DR, et al. Consumer talcums and powders: Mineral and chemical characterization. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1976;2(2):255–84. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15287397609529432

- Tran TH, Steffen JE, Clancy KM, Bird T, Egilman DS. Talc, asbestos, and epidemiology: Corporate influence and scientific incognizance. Epidemiology. 2019;30:783–8. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/epidem/fulltext/2019/11000/talc,_asbestos,_and_epidemiology__corporate.2.aspx

- Gordon RE, Fitzgerald S, Millette J. Asbestos in commercial cosmetic talcum powder as a cause of mesothelioma in women. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2014;20(4):318–32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/2049396714Y.0000000081

- Hollinger MA. Pulmonary toxicity of inhaled and intravenous talc. Toxicol Lett. 1990;52:121–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4274(90)90145-C

- Karwowski MP, Morman SA, Plumlee GS, Law T, Kellogg M, Woolf AD. Toxicants in folk remedies: implications of elevated blood lead in an American-born infant due to imported diaper powder. Environ Geochem Health. 2017;39(5):1133–43. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10653-016-9881-6

- Randive DS, Bhinge SD, Jadhav NR, Bhutkar MA, Shirsat MK. Carbon based kajal formulations: Antimicrobial activity and feasibility as a semisolid base for ophthalmics. J Pharm Res Int. 2020;32:62–74. Available from: https://journaljpri.com/index.php/JPRI/article/view/1461

- Chhablani J. Combined photodynamic therapy and intravitreal ranibizumab as treatment for extrafoveal choroidal neovascularization associated with age-related macular degeneration. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2010;3(2):99–100. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-620x.64241

- Tiffany-Castiglioni E, Barhoumi R, Mouneimne Y. Kohl and surma eye cosmetics as significant sources of lead (Pb) exposure. J Local Glob Health Sci. 2012;2012(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5339/jlghs.2012.1

- Mustehasan, A. M.; Naushin, S.; Urooj, M.; Husain, G. M. Overview of Sang-e-Surma (Antimony Sulphide or Lead Sul-Phide): A Mineral Origin Unani Drug; 2022; Vol. 7.

- Al-Ashban RM, Aslam M, Shah AH. Kohl (surma): A toxic traditional eye cosmetic study in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 2004;118(4):292–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2003.05.001

- Al-Saleh I, Mustafa A, Dufour L, Taylor A, Hiton R. Lead exposure in the city of Arar, Saudi Arabia. Arch Environ Health. 1996;51(1):73–82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00039896.1996.9935997

- Sathyanarayana S, Karr CJ, Lozano P, Brown E, Calafat AM, Liu F, et al. Baby care products: Possible sources of infant phthalate exposure. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):e260–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3766

- Robinson VC, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, Marks JG, et al. Final report of the amended safety assessment of sodium laureth sulfate and related salts of sulfated ethoxylated alcohols. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29(4):151S–161S. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1091581810373151

- Nikle A, Ericson M, Warshaw E. Formaldehyde release from personal care products: Chromotropic acid method analysis. Dermatitis. 2019;30(1):67–73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/der.0000000000000434

- Backe WJ. A novel mass spectrometric method for formaldehyde in children’s personal-care products and water via derivatization with acetylacetone. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2017;31(12):1047–56. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7874

- de Groot AC, Flyvholm MA, Lensen G, Menné T, Coenraads PJ. Formaldehyde-releasers: relationship to formaldehyde contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:63–85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01582.x

- Symanzik C, Weinert P, Babić Ž, Hallmann S, Havmose MS, Johansen JD, et al. Skin toxicity of selected hair cosmetic ingredients: A review focusing on hairdressers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jul 1;19(13):7588. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137588

- Lim TY, Poole RL, Pageler NM. Propylene glycol toxicity in children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Oct-Dec;19(4):277–82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5863/1551-6776-19.4.277

- Wang J, Liu Y, Kam WR, Li Y, Sullivan DA. Toxicity of the cosmetic preservatives parabens, phenoxyethanol and chlorphenesin on human meibomian gland epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2020;196:108057. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2020.108057

- Cullen MR, Balmes JR, Robins JM, Smith GJW. Lipoid pneumonia caused by oil mist exposure from a steel rolling tandem mill. Am J Ind Med. 1981;2:51–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.4700020109

- Spickard A, Hirschmann JV. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia. Chest. 1994;154:686–92. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8129503/

- Pirow R, Blume A, Hellwig N, Herzler M, Huhse B, Hutzler C, et al. Mineral oil in food, cosmetic products, and in products regulated by other legislations. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2019;49:742–89. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408444.2019.1694862

Figures:

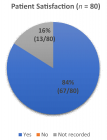

Figure 1

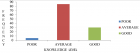

Figure 2

Similar Articles

-

Development of Latent Fingerprints Using Food Coloring AgentsKallu Venkatesh,Atul Kumar Dubey,Bhawna Sharma. Development of Latent Fingerprints Using Food Coloring Agents. . 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001070; 8: 104-107

-

Toxic Components in Baby Care Products – A Comprehensive ReviewAvinav Jha*. Toxic Components in Baby Care Products – A Comprehensive Review. . 2025 doi: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001077; 9: 029-036

Recently Viewed

-

Maternal and perinatal outcomes of uterine rupture in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of CongoJacques Ngoy Kitenge,Olivier Mukuku*,Xavier K Kinenkinda,Prosper L Kakudji. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of uterine rupture in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2020: doi: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001067; 3: 136-141

-

Effect of sperm DNA fragmentation on ICSI outcome: A prospective studySaravanan Lakshamanan,Saravanan Mahalakshmi,Harish Ramya,Sharma Nidhi*. Effect of sperm DNA fragmentation on ICSI outcome: A prospective study. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2020: doi: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001065; 3: 127-131

-

Forensic analysis of private browsing mechanisms: Tracing internet activitiesHasan Fayyad-Kazan*,Sondos Kassem-Moussa,Hussin J Hejase,Ale J Hejase. Forensic analysis of private browsing mechanisms: Tracing internet activities. J Forensic Sci Res. 2021: doi: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001022; 5: 012-019

-

A study of coagulation profile in patients with cancer in a tertiary care hospitalGaurav Khichariya,Manjula K*,Subhashish Das,Kalyani R. A study of coagulation profile in patients with cancer in a tertiary care hospital. J Hematol Clin Res. 2021: doi: 10.29328/journal.jhcr.1001015; 5: 001-003

-

Viral meningitis in pregnancy: A case reportRuth Roseingrave*,Savita Lalchandani . Viral meningitis in pregnancy: A case report. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2020: doi: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001063; 3: 121-122

Most Viewed

-

Evaluation of Biostimulants Based on Recovered Protein Hydrolysates from Animal By-products as Plant Growth EnhancersH Pérez-Aguilar*, M Lacruz-Asaro, F Arán-Ais. Evaluation of Biostimulants Based on Recovered Protein Hydrolysates from Animal By-products as Plant Growth Enhancers. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2023 doi: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001104; 7: 042-047

-

Sinonasal Myxoma Extending into the Orbit in a 4-Year Old: A Case PresentationJulian A Purrinos*, Ramzi Younis. Sinonasal Myxoma Extending into the Orbit in a 4-Year Old: A Case Presentation. Arch Case Rep. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001099; 8: 075-077

-

Feasibility study of magnetic sensing for detecting single-neuron action potentialsDenis Tonini,Kai Wu,Renata Saha,Jian-Ping Wang*. Feasibility study of magnetic sensing for detecting single-neuron action potentials. Ann Biomed Sci Eng. 2022 doi: 10.29328/journal.abse.1001018; 6: 019-029

-

Pediatric Dysgerminoma: Unveiling a Rare Ovarian TumorFaten Limaiem*, Khalil Saffar, Ahmed Halouani. Pediatric Dysgerminoma: Unveiling a Rare Ovarian Tumor. Arch Case Rep. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001087; 8: 010-013

-

Physical activity can change the physiological and psychological circumstances during COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative reviewKhashayar Maroufi*. Physical activity can change the physiological and psychological circumstances during COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. J Sports Med Ther. 2021 doi: 10.29328/journal.jsmt.1001051; 6: 001-007

HSPI: We're glad you're here. Please click "create a new Query" if you are a new visitor to our website and need further information from us.

If you are already a member of our network and need to keep track of any developments regarding a question you have already submitted, click "take me to my Query."